“Actors in white linens shower the crowd with tiny flower petals. This night’s itinerant theatre performance has transformed into a banquet in which actors and audience are no longer separated, the barriers gone. On these ancient stones is laid out a banquet of laughter, food and wine, and all are invited.”

Tables covered with flying white cloths and laden with food appear out of nowhere for a crowd of several hundred in a piazza at the edge of the cliff, in the oldest part of this old city. Strings of dazzling lights stretch across the square as a dove flies up and the bells of the 1,000-year-old church of San Giovenale clamor in the black night. Actors in white linens shower the crowd with tiny flower petals. This night’s itinerant theatre performance has transformed into a banquet in which actors and audience are no longer separated, the barriers gone. On these ancient stones is laid out a banquet of laughter, food and wine, and all are invited. This is the culmination of our journey through the streets of Orvieto, our revivification of medieval city theatre.

Orvieto sits high on a cliff of hardened volcanic ash – tufa – in the Umbrian hills about an hour north of Rome. Of Etruscan origin, the city came to be known as Urbs Vetus as people whose ancestors had been exiled by the Romans slowly returned to the “old city” during the Dark Ages. The name stuck and evolved into Orvieto. Inside the rock on which the city is built is a labyrinthine network of several thousand caves and cisterns, a whole invisible life beneath the visible. Many of the caves along the cliff face are lined with thousands of ancient niches, carved in checkerboard patterns as nests for domesticated doves. These dovecotes are called colombari. The doves, their eggs, their poop, provided centuries of ‘sustainable agriculture’ for the city’s inhabitants. Dominating the entire cityscape is its Duomo, an early-14th-century cathedral richly decorated with relief-sculptures of the story of salvation from Creation to Last Judgment, and huge areas of mosaics backed in gold, creating a façade like a vast shield of light.

Just as Orvieto is an ancient city in the modern word, so our project of creating “medieval mystery plays for the 21st Century” seeks to connect the medieval roots of theatre with contemporary life. The core group of performers – Italian and American – are members of La Compagnia de’ Colombari, the international ensemble I formed in Orvieto and New York City. But we involve people of all ages in our itinerant productions, children from the local dance school, the boy drummer from the town band, professionals from the town’s two theaters. The working title for this ongoing project is Strangers and Other Angels.

Orvieto turns out to be a kind of ground zero for the English medieval drama and hence the re-emergence of Western theatre. Religious dramas, or sacre rappresentazioni, were staged in cities across Europe, originally as an outgrowth of the liturgy. Many were connected with the feast of Corpus Christi established by Pope Urban IV from his residence in Orvieto itself in 1264. The new holy-day celebrated the mystery of the Incarnation – of God’s presence in creation, in Jesus his son, in the elements of holy communion – and was prompted in part (as local legend would have it) by the Eucharistic miracle that occurred in nearby Bolsena in 1263. There, at the Elevation of the Host during a mass celebrated by a visiting priest, drops of blood fell from the wafer of communion bread onto the altar cloth, or corporal. The liturgy for Corpus Domini (as the holiday is also called) was prepared at the pope’s request by none other than Thomas Aquinas, then in residence at the Dominican monastery in town.

The annual processing of the relic of the Holy Corporal around the city has continued for centuries as the pivotal event of Orvieto’s calendar, an immense solemn parade rich with pageantry with hundreds of local participants in medieval costume and thousands of visitors from around the world. But only in England was this play of Corpus Christi transformed into entire cycles of biblical history, with 20 or 30 episodes from Creation to Doomsday performed in parade fashion in the squares of towns such as York, Chester, Coventry and Wakefield. Our intention has been to bring back the English contribution to its Italian source, reuniting religious parade with religious theater.

I had been interested in the medieval plays since my undergraduate studies at Gordon College, fascinated by the sheer scale of their theme and plot, the large, resilient imagination that placed irreverence side by side with the holy, the playful game aesthetic, the populist spirit of these plays that pressed outside the church walls into the streets. Our original title for the Colombari project was Laude in Urbis, laude being a Latin spin on “game” and “praise,” urbis a Latin play on “city” and “world”. The phrase captures our vision of a recovery of the medieval-city model of the Corpus Christi drama, re-envisioned for a modern global audience.

Our script is mostly drawn from the English mystery play cycles, arranged in its sequence by John Skillen, translated into Italian by Walter Valeri, with adaptations by playwrights such as Mark Stevick. Along with these plays I inserted disparate pieces of texts, both old and new, by such writers as Zora Neale Hurston, Erik Ehn, Carl Hancock Rux and Dante Alighieri, as well as a Hebrew psalm, a Latin passage from the Vulgate and an Italian text from the 1200s. And there are songs, fusing gospel and jazz with modern classical idioms, in English, Italian, Latin and Hebrew.

In our contemporary mystery play, God is on the move, showing up in human affairs via angels and strangers. We follow Jesus through the streets in the frame play, “Christ’s Appearance to the Disciples,” from the Coventry cycle. Drawn from the Gospel of Luke, the now-resurrected Jesus joins two disciples walking on the road to Emmaus. When the two wonder how this stranger has missed the news about the crucifixion of the one they hoped was the Messiah, he (in the drama) sings a new song “Don’t you remember?” Jesus takes the disciples – and by extension, the audience – on a passeggiata during which he asks them to remember five moments of divine intervention: “Creation,” “Noah,” “Abraham and Isaac,” “Second Shepherds’ Play” and “Descent into Hell.” The company stands by, some to play all the parts of humankind, others to portray the Holy Trinity and the angels. An intermezzo enacts a song, an argument, a dance (or whatever naturally extends from the end of the previous play), engaging the audience while it moves from one location to the next.

The making of Strangers and Other Angels feels more like a Fellini film than a piece of theatre. There are sheep to wrangle, doves to feed, children to keep entertained, weather and cars to negotiate, permissions to get, bystanders to bring up to date, not to mention corralling the professional actors who are being asked to hurry up and wait (without a trailer). The Orvietani – whose city streets have become our daily rehearsal hall – humor us in our theatrical exercises. We are surrounded by a cacophony of the market, the orchestra of life that brings a welcomed infusion of city energy. Yet the challenge in making the piece was always walking the line between order and chaos – it’s part of the game.

How are we to breathe new life into these old plays? I was looking for dynamic modern spiritual expression. I turned to writers like Ehn and Rux. For the play Abraham and Isaac, Ehn refashioned Abraham’s response to God (at the end of his test of faith) into an astonishing piece of poetry: “I’ve already turned you inside out in my mind. I’ve already painted secret signs in angel blood….” For the Ark play, Rux wrote a witty song giving a hilarious account of Noah’s task: “And the Lord said / Noah Noah / in his 600th year / ... You, Japheth, Shem and Ham / gather all you can / all the beasts of the fields / string ‘em up to the wheels / make them an indoor barn…” Then I turned to American spirituals, as well as James Weldon Johnson’s exuberant poem “The Creation” from God’s Trombones; an exhilarating piece of a sermon from Hurston’s 1934 novel Jonah’s Gourd Vine; the final passage in Dante’s Paradiso; and part of a poem by Pope John Paul II. In this way, the dramatic trajectory of the original fused together the new and the old.

Since this theatrical passeggiata begins at the edge of twilight, we needed lighting that moved. Designer Chris Akerlind found a solution: Instead of hanging lights in the traditional way, he used powerful hand-held spotlights in the piazza to sculpt entire scenes. For the intermezzo movements, Chris devised 12 long portable battery-powered lightsticks to illuminate the moving actors.

To convey the radical nature of Jesus’s birth, the Nativity scene has to be carved out of the crowd. For an audience to be involved in the abject poverty and emotional richness of the event, the birth has to happen suddenly right in their midst – out of nothing. My visual inspiration is the chiaroscuro effects of Rembrandt and Caravaggio, so the baby in arms becomes the source, rather than the object, of the light. Peter Ksander (another lighting designer) swirls a powerful, unwieldy light source very, very slowly while actor Patrice Johnson (playing Mary) gently cradles and rocks the light. There is no doll. Its rays land on the children (fresh from playing the sheep in the “Second Shepherds’ Play”), who have formed a circle in the midst of the audience. All eyes are on Mary’s strikingly serene face. The Nativity star is held high by a young Orvietana actor while the Holy Trinity and the angels look on. From Trazana Beverly (playing the role of God) comes a gospel song: “Mary had a baby ...,“ the phrase repeated until the entire company joins in the chorus.

The “Creation” story, with its focus on the breath of life, has to happen in front of the Duomo, the heart of the city. I was duly warned about the acoustics on the steps of the Duomo – God would not be heard, people warned me, because the piazza was too wide and deep. Tell that to Trazana Beverly! One Thursday morning we take our rehearsal to the steps of the Duomo in a tourist-filled piazza. Trazana strides up the steps and begins speaking the words of Johnson. The gelato-carrying tourists turn to listen as her fierce-tender voice soars through the vast piazza and upward to the Duomo’s peak. In Trazana, we have an actress who doesn’t need a microphone.

As much as any other, this moment is a metaphor for our project: An African-American actress, a force of nature, in front of one of the towering icons of medieval Europe. In my mind, they are an equal match. Yet it isn’t a competition – it is a joining, a meeting, an intertwining, each element giving breath to the other.

Like engaging a community, making a community takes work. A team needs to practice its moves. A fundamental step is the process of learning each other’s language. All the American actors are required to speak some lines in Italian. When Patrice Johnson, from Los Angeles, plays the part of Eve in the “Creation” story in Italian, the Orvietani audience is visibly moved. “Adamo, Adamo,” she shouts, calling for Adam, and even improvises a little: “Mio marito, mio caro” (my husband, my dear)!

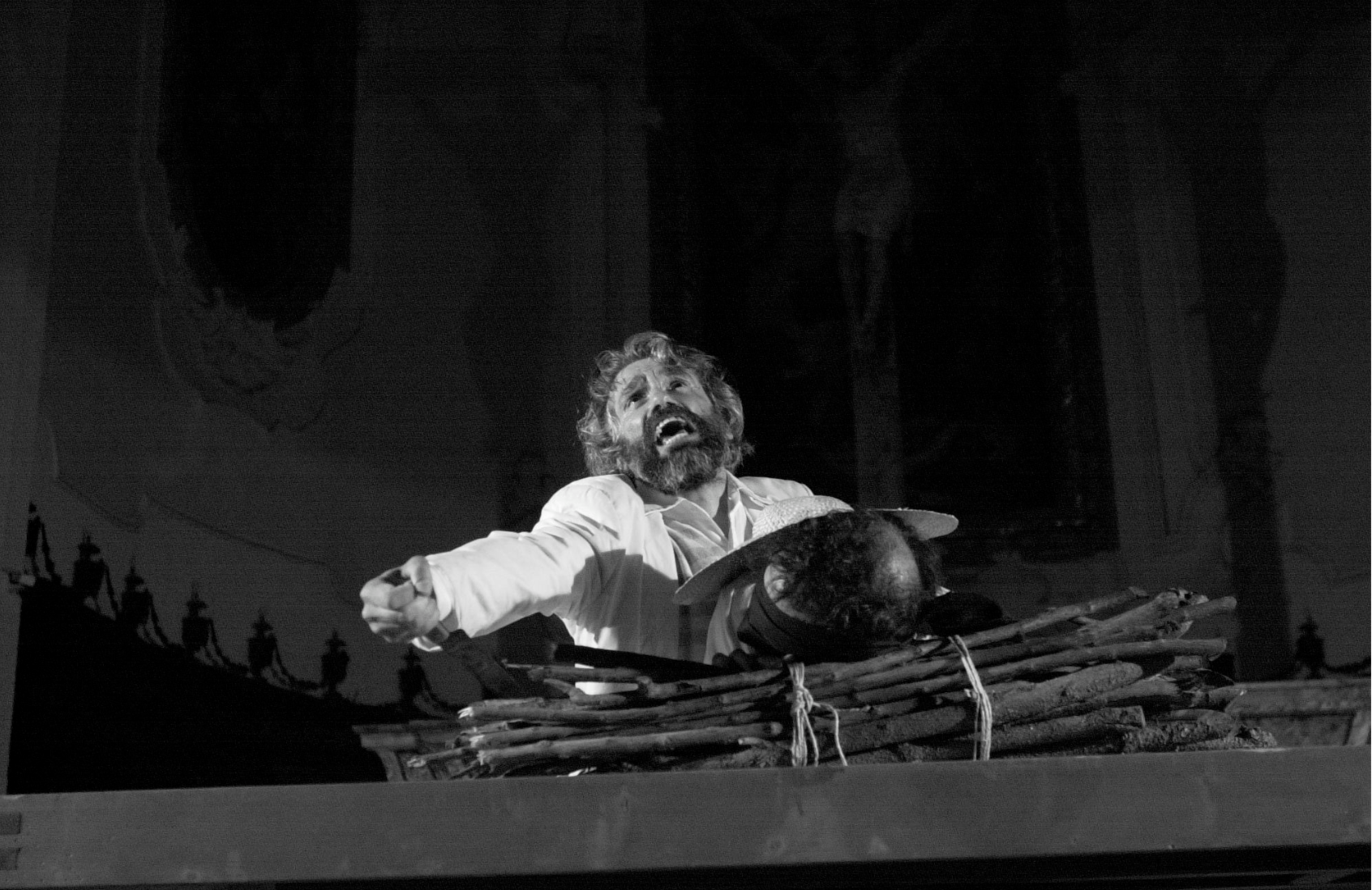

The Italian actors have it easier, using their native language but occasionally improvising in English in some comical sections. For Gianluca Foresi, from Orvieto, this facilitates a populist, sometimes startling fusion of the irreverent and the holy. In the story of Noah, when God calls him to build an ark, Noah accepts, but his spiritual excitement is ruined by a voice from the domestic front – his wife’s. Working from the giullare (jester) tradition, Foresi freely moves from English to Italian for certain choice moments. Our 10 light carriers are in hot pursuit as the squabbling Mr. and Mrs. Noah, locked in a bitter, hilarious battibecco (quarrel), walk two blocks from the Piazza del Duomo, banging angrily on doors en route to the site of the ark. When the audience arrives, they see Mrs. Noah (played by Elisabetta Moretti) sitting on the roof knitting and Mr. Noah standing on a ladder making finishing touches to the ark – both muttering to themselves about the other.

The muttering eventually devolves into raucous insults. Noah shouts to his wife: “Conservatista! Comunista! Animalista! Turista!...” Pleading for her understanding, Noah says in a mix of English and Italian: “I’m not working just for me. I’m working for you! Lavoro per te, lavoro per tutti, for e-v-e-r-y-b-o-d-y!” With the deluge imminent, wearing a rain slicker and using a megaphone, Noah calls the animals of the world and urges his wife to go inside.

But Mrs. Noah remains unmoved. Appearing suddenly, the Holy Spirit (played by a young Orvietano teenager, Matteo Dragoni) picks up massive water pistols and squirts Mrs. Noah out of her certitude. Finally she goes into the ark. Out of all the earthly fuss and madness, stepping out of his usual comic role, Foresi’s Noah achieves a sacred moment: He leads the entire company (which has turned into a great herd of animals) in a prayer of gratitude to God. In the 2006 version Jeanette Thompson sings “Oh, the deep, deep love of Jesus,” her enormous voice evoking the De Profundis, the voice of God rising from the depths.

The collision of cultures is for me an opportunity to be seized. The reader may think I’m over the edge, but I look at Fra Angelico’s painting of the Last Judgment and hear jazz. (Check out the angel at far left with hand on hip in a syncopated jazz pose, leading the blessed into heaven in the painting in the Museo di San Marco, Florence.) Our opening song, “Don’t You Remember?”, driven by trombone and punctuated by tuba, comes from the Dixieland tradition and sets the tone for the rest of the evening. Another melding opportunity is creating a bar mitzvah for Isaac in the “Abraham and Isaac” story. The idea is met with blank looks by the choreographers Claudia and Valentina Marini and the Orvieto dancers, something outside their experience. But once we play the klezmer-based music, one actor, Elisabetta Spallaccia, shouts the “Oopla!” and gets it on the first try – the clapping, the rhythm, the shouts, the spirit. Recalling the rehearsals, Elisabetta says: “From the first moment I didn’t have a single difficulty. Communication came spontaneously. It was as if we all spoke the same language, on the human level and the professional.”

For our African-American actors, theatre-in-the-streets in Orvieto brings other challenges. Says Patrice Johnson, of Jamaican descent, about her experience: “When I first got to Orvieto, it was obvious there were not many black people there. Though people were polite, I would inevitably catch the stare of children who would either want to touch me or were actually frightened.”

All of that changes, however, the night she performs Laude in Urbis for the community. Patrice goes on: “I played iconic figures in religious history – a black Mary and a black Eve. We sang and acted and interacted with the natives of Orvieto, and the magic of theatre that always breaks down barriers happened for us that night. The people gave us their hearts and took in the cast, including the black actors, as we traveled through the streets and led them through Hell and back into the open piazza. There the entire cast showered them with blossoms of rose petals.”

At the banquet, Patrice recalls, the people of Orvieto “who were until this night very polite and removed, started hugging and kissing me effusively on my face and forehead, at times lifting me off my feet. I was no longer someone or some stranger to fear. I was known to them and by all of them, intimately and in an instant.”

Strangers and Other Angels begins and ends at the piazza, where our international company finally merges with the audience in a feast. The piazza becomes the scene of a great convergence – the vast history of art and architecture in Italy and the music of the USA, specifically jazz, blues, gospel, spirituals. I remember hearing the critic Stanley Crouch say on a television interview, “Mahalia Jackson and the early Italian Renaissance – they’re the same thing.” This convergence, this collision, this breaking of bread shows how right he was.

In Strangers and Other Angels, our subject is God and man in search of one another, but our medium is the community. The Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel in his book The Sabbath says: “We share time, we own space. Through my ownership of space, I am a rival of all other beings; through my living in time, I am a contemporary of all other beings. We pass through time; we occupy space. We easily succumb to the illusion that the world of space is for our sake, for man’s sake. In regard to time, we are immune to such an illusion.”

When Trazana Beverly steps in front of the Duomo and speaks, I hope to capture – or at least to touch – Heschel’s vision of the eternal now, of a shared time that gives us a foretaste of an eternal sabbath.

Karin Coonrod (MFA Directing, Colombia University; recipient of the Gordon College Alumnus of the Year award) has been widely acclaimed for her productions of Shakespeare in New York and elsewhere. She was invited to direct The Merchant of Venice in the Jewish Ghetto in Venice in July 2016 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. A recent critic in the New York Times (Oct 24, 2015) calls Coonrod “a theater artist of far-reaching inventiveness,” praising the work she herself created from the writings of Queen Elizabeth I. Entitled texts&beheaings/ElizabethR, Coonrod’s play debued at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in the fall of 2015. Coonrod created the Compagnia de’ Colombari in Orvieto to perform versions of the medieval mystery plays from 2004 to 2006 through the streets and piazzas of Orvieto, restoring drama to the town’s Festival of Corpus Christi. The Colombari’s staging of stories by Flannery O’Connor and Gertrude Stein, the poetry of Walt Whitman, Isaak Dineson’s Babette’s Feast, and the plays of Hungarian-Romanian playwright András Visky have all received critical acclaim.

Photograph credits to Massimo Achille